Funded by the National Science Centre, call OPUS-22, grant no. UMO-2021/43/B/NZ1/01436

Total funding: 1 817 000,00 PLN

Timeframe: 03/10/2022-02/10/2025

The purpose of this project is to investigate the population dynamics of antibiotic-resistant mutants of the bacterium E. coli immediately after their emergence due to spontaneous mutations. It takes time for a new mutant cell to develop resistance to a drug, and what happens during this transition period is not fully understood. The project fills a gap between the well-studied genetics of resistance (which mutations cause resistance?) and phenotypic characterization of fully matured mutants (growth rates at different antibiotic concentrations).

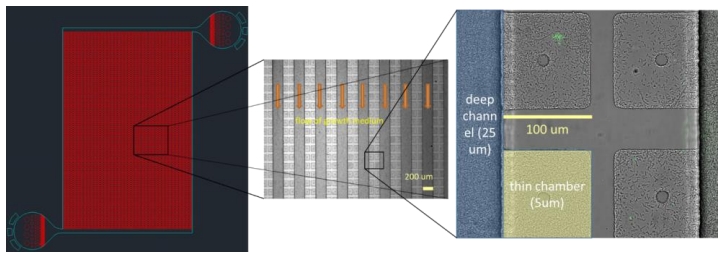

The project has two components: (i) development of a microfluidic culture device (“MegaMicroplate”) suitable for optical screening of ∼ 109 cells to identify 1 − 10 spontaneous mutants and follow their growth over a few generations, (ii)

investigation of the transition from the sensitive to the resistant phenotype following a genetic mutation. We will also use mathematical modelling to interpret the data and to predict its significance for bacterial infections.

Bacteria can rapidly evolve resistance to virtually all known antibiotics, sometimes in a matter of hours. Fundamental research into the process by which bacteria acquire resistant mutations, and how such mutations spread in bacterial populations has the potential to enable the development of new, “evolution-resistant” antimicrobial therapies. Bacteria become resistant to antibiotics through several different mechanisms. In this project we focus on de novo mutations in genes that code enzymes targeted by antibiotics. Such mutations are known to occur during human infections. However, what exactly happens between the mutational event (a DNA alteration) and the expression of a new, altered phenotype is not well understood. It is now accepted that the process involves a delay called phenotypic lag, has never been measured in spontaneous de novo mutants.

The project promises a technological innovation and a solution to an important biological problem of mutagenesis proccess. To date, the most comprehensive study of phenotypic lag relied on electroporating plasmids carrying resistant mutations to avoid the technical difficulty of detecting and following de novo mutations. Our experimental approach will enable us to directly probe the transition from a genetic mutation to phenotypic resistance. We will also obtain growth rates of early mutants. Our quantitative experiments will help us develop better models of bacterial population dynamics required for predicting the course of microbial evolution.